Why Enterprises Overfund Failure and Underfund Prevention

Most reliability debates start with technology and end with frustration.

——————————————-

Want to try it out? Take the 5-minute Reliability U-Curve Assessment → reliabilityeconomics.com/benchmark

———————————————

Do we need more redundancy?

More automation?

More “nines”?

But after working with large enterprises for years, I’ve come to a different conclusion:

Most organizations don’t have a reliability problem.

They have a failure-funding problem.

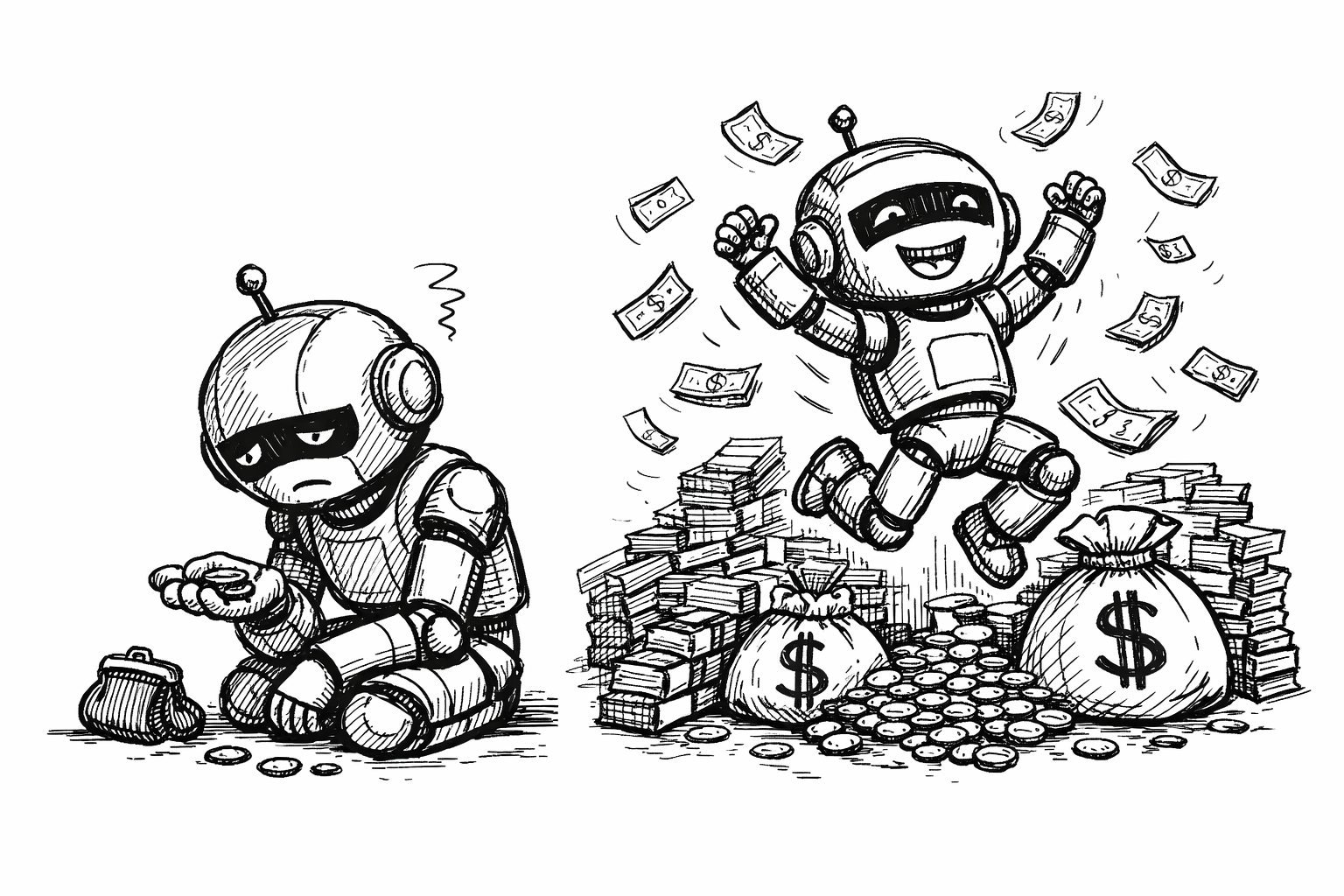

The hidden bias in how reliability gets funded

In theory, organizations want stability, resilience, and predictable delivery.

In practice, money flows very differently.

There are two fundamentally different cost buckets:

Failure cost (reactive): incidents, war rooms, hotfixes, customer impact, escalation overhead

Prevention cost (proactive): SLOs, automation, resilience patterns, testing, observability, compliance-by-design

Only one of these is visible and urgent.

Failure cost:

shows up as outages,

triggers executive attention,

creates immediate pressure to “do something.”

Prevention cost:

is mostly invisible,

pays off over time,

competes with feature delivery and short-term KPIs.

So organizations do what humans and systems always do under pressure:

they optimize for what hurts now, not for what compounds later.

Why “we’ll fix it in incident response” feels rational (but isn’t)

From a budgeting perspective, failure remediation feels safe:

Incidents are real.

Customers are angry.

Regulators are watching.

Action is justified.

Prevention, on the other hand, requires belief:

belief that future incidents will be avoided,

belief that automation will pay off,

belief that today’s effort reduces tomorrow’s cost.

That belief is hard to defend in quarterly planning cycles.

The result is a predictable pattern:

incident response teams grow,

processes accrete,

coordination overhead increases,

and yet reliability outcomes improve only marginally.

This is how organizations end up spending more every year on failure without ever feeling “done.”

The reliability U-curve (in one sentence)

As reliability improves:

failure cost goes down,

prevention cost goes up,

and total cost forms a U-shape.

The bottom of that curve is the point where total spend is minimized.

Most enterprises never intentionally look for that point.

They drift along the curve driven by incidents, not economics.

Why this is not a failure-mode or probability model

A common (and valid) objection is:

“Failure costs depend on likelihood, failure modes, SLAs, and contracts. You can’t aggregate this.”

That’s true, at the failure-mode level.

But this is not a failure-mode model.

It’s a portfolio-level diagnostic designed to answer a simpler question:

Are we structurally overpaying for failure compared to prevention for this service or journey?

At that level:

recurring operational failures already “price in” likelihood,

black-swan events should be treated separately and selectively,

and perfect modeling is often the enemy of usable decisions.

This is not about precision.

It’s about direction.

What happens when you make both sides visible

When organizations put failure cost and prevention cost side by side, something interesting happens.

They realize that:

incident labor and coordination time dominate downtime cost,

release delays and context switching are real economic drag,

compliance overhead is often paid manually instead of being automated,

and prevention is often far cheaper than the failures it could eliminate.

In many large environments, it’s not unusual to see:

monthly failure cost 5–10× higher than prevention spend

for a single tier-1 service.

At that point, the conversation changes.

Not because of SRE ideology, but because of economics.

The shift that actually matters

This isn’t about chasing “five nines.”

It’s about shifting from:

funding failure because it’s visible,

tofunding prevention because it’s cheaper.

That shift only happens when:

engineering brings data about failure drag,

finance helps frame recurring cost,

leadership sets explicit risk tolerance.

Reliability improves not because teams try harder, but because the system starts rewarding the right investments.

A practical starting point

You don’t need a perfect model to begin.

Pick:

one service or customer journey,

estimate monthly failure cost,

estimate monthly prevention cost,

sanity-check outcomes via SLOs or error budgets.

The goal is not to be “right.”

The goal is to stop being blind.

Final thought

Enterprises rarely fail because they don’t care about reliability.

They fail because:

failure is loud,

prevention is quiet,

and budgeting systems are wired to respond to noise.

Until we change that, we’ll keep getting better at fixing incidents, and worse at preventing them.

→ If you want a practical starting point, message me “INVERSION” and I’ll share a lightweight diagnostic to estimate your current position on the U-curve and where the optimum likely sits.

→ We explore these ideas in much more depth in our book, Mastering Site Reliability Engineering in Enterprise, a complete guide to building resilient, chaos-tolerant systems, available on Amazon and Springer.

Book (Amazon): Mastering Site Reliability Engineering in Enterprise now on amazon.com

Book (Springer): Mastering Site Reliability Engineering in Enterprise on Springer